@ The Narrators (podcast)

A reflection on change, desire, choice, and the stories we tell about ourselves

Struggles in re-writing the narrative of my life

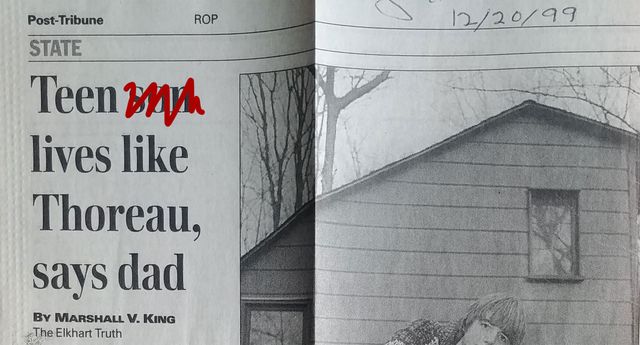

Last week, my dad sent me a newspaper clipping from the Gary (Indiana) Post-Tribune – December 20, 1999. There’s a photo of me at 17, a senior in high school, leaning against a mountain bike. I’m wearing baggy jeans, socks, and Birkenstock. Because it’s the 90s and I’m into fashion.

To quote the caption, I had been living rustically since September, when I moved into a small cabin at the edge of my parents farm, along the Elkhart River. An experiment in simple living according to the article. That’s true. I had a hand pump over the sink, a wood stove for heat, an outhouse, some oil lamps, and a typewriter for my homework.

I read a lot of Thích Nhất Hạnh in that cabin, and wrote some truly mediocre poetry. What a writer friend referred to recently as poemy poems, about stones.

The article also says I had aspirations towards a monastic life after high school. I don’t remember serious monastic plans exactly, but now I’m a software developer, and a musician living in a loft just off South Broadway. It’s not rustic or monastic. When I want to write mediocre poetry now, I walk down to the Bardo coffee house and listen to Lizzo on my Airpods. What happened?

Here’s the headline from the article: Teen son lives like Thoreau, says dad.

Teen son. I couldn’t read the rest of the article. I went back to watching Project Runway. I don’t want to spoil anything, but Bishme is great, and Garo’s a total hack.

So I’ve been thinking a lot about change. Big change . Identity change. I was raised Mennonite, but at some point that label stopped making sense. I was raised a boy, too, but that didn’t stick. I was also married, once – that’s another story. But I remember talking to my aunt during the divorce. This was 2004, maybe 2005. We’re sitting around her kitchen table late at night, and she says You can start dating again once your ex doesn’t come up in daily conversation – once the stories you tell don’t involve her.

It’s not a perfect rule – date whenever you want to – but I still love something about that: using our internal narrative as a guide. Not in some spiritual sense, but very practically. My identity is a story that I tell to myself, and to you, and I can change the way I tell that story, but it takes time to write that new material. Or to live that new material.

In this case, material without my ex wife – which is awkward, ‘cause here I am 15 years later, standing on stage, talking about her.

Sorry Erin! I guess I’m not ready to date yet!

But back then, living in that small community, small Mennonite college town, everyone knows me – knows us. Everyone needs to hear the story, so I tell it over and over for months. And it’s clear, every time, that I’m being cross-examined. I’ve done something bad, and I have to defend my actions. And I can do that. I can tell that story, but it feels gross.

Why do I need to explain myself to you? It was bad and I left. Trust me.

And I think about smaller changes, too. I remember moving to Denver – driving in on 76 for the first time. This is August 2007 now, and I remember the sun setting over the mountains due west, and storm clouds rolling in from the southwest – lightning flashing behind a city skyline.

The scale of it! The expanse. To see that storm from a distance, between a skyline and a mountain range. That’s not a thing in Indiana. It feels like space and possibility. So much room for something new. So much more to the world than right here or right now or just me. It felt like home. Driving home. A home I’d never been to?

I would sometimes walk down 16th street at night just to feel invisible – part of a crowd. Someone else might frame this as a move from the peaceful woods to the bustling city, but my experience was the opposite. Being unknown gave me room to think, and space to change – emotional space the cabin couldn’t provide.

And then I would meet people, and they’d ask where I’m from, and they’d mean before Denver, and I guess Indiana? But it felt wrong, like the wrong question. Not because Indiana is bad – this was before Mike Pence – but because, I don’t know, I was eager for my narrative home to catch up with my experience of home.

And a year later I was on the road back through the Midwest, touring a theater production with new friends. And every night, after the show, audience members would ask where we came from. I was so happy. I’m from Denver! I mean, it’s super silly – this gentrified mess of a city. Shrooms are legal, but being homeless is a crime.

Still, at that point, I guess: home is important. It gives your story context. The frame matches the content.

But what happens to that old story when the new one comes along? Suddenly we’re correcting everyone. I’m not Mennonite anymore. I’m not married. I’m not a boy. You’re thinking of Yesterday Me! Yester-me! She’s a whole different person! And again, coming out – this is 2015 now – I’m asked to explain and defend my actions.

It was bad, and I left. Trust me. This frame matches the content.

And the story we expect to hear – want to hear – is that born-this-way narrative. Trapped in the wrong body, whatever that means. This body is mine. It just needed some estrogen up in there, that’s all. Anyway, I remember being that boy in that cabin, talking to the South Bend Post-Tribune about simple living and monastic life. I was that titular teen son.

But I do also remember – all along – how much I wasn’t a boy when I lived in that cabin, and talked to that reporter. I mean, obviously: it was me in the cabin, and I’m not a boy. We grow. We change. We have to tell a new story, and bring people along. We have to get our stories straight.

Not straight, straight, but straight. You know.

I wasn’t born this way, I grew into it – like every child grows into their adult narrative. I chose it. I looked at my options, and chose estrogen, and I’m proud of that choice. It’s ok to have choice. Choice is a good thing. I’m tired of the narrative that my queerness is ok as long as I didn’t want it. I wanted estrogen, and I got it. If you want estrogen, you can have it too.

All of that is true, and also. Also I was born with all of this inside of me. Born to grow into this desire, this choice. Born to choose this way. Because biology and choice aren’t at odds, they’re both part of life – being alive. Life isn’t static, it moves and changes. As it moves, we tell new stories. We take a snapshot, we add a caption, and we publish it in the Gary Post-Tribune. One moment in time. One boy who’s also a girl. One boy who will grow into a woman.

Anyway, I got Erin to read the article out-loud to me – translate it so I could hear myself in the story. “Teen daughter lives like Thoreau, says dad. Miriam needs space and quiet, and she’s got that now.” And it’s interesting to read that – or hear it – knowing what I know: about myself, about my loud father, about being introverted, and an activist, a writer, caring about the world – what I’ve done with those feelings, those beliefs. Not letting them go, but letting them grow with me, to become who I am now.

And, well yester-me, fuck. The world hasn’t gotten better. Shit’s bad, and you’ll have to keep fighting. But you’ll be glad to know: you get to be a girl, you love it, you’re not from Indiana anymore, and you finally – after many failed u-haul-lesbian relationships – you finally live on your own, not entirely monastic, surrounded by friends, with a wonderful partner just down the hall.

If I’m still allowed to date after this.